MXR’s Eddie Van Halen signature phaser, flanger, and wah pedals made elements of Eddie’s tone available and affordable to the masses. But one of the most critical components in creating his “Brown Sound” is copious amp overdrive. If you don’t have a vintage Marshall Super Lead or an EVH amp (both expensive propositions), the right overdrive pedal is an effective shortcut. And the MOSFET-driven MXR 5150 Overdrive—which was designed by Bob Cedro with input from Mr. Van Halen himself—is a stab at harnessing Eddie’s hot-rodded, high-gain sounds in a pedal.

MXR’s Eddie Van Halen signature phaser, flanger, and wah pedals made elements of Eddie’s tone available and affordable to the masses. But one of the most critical components in creating his “Brown Sound” is copious amp overdrive. If you don’t have a vintage Marshall Super Lead or an EVH amp (both expensive propositions), the right overdrive pedal is an effective shortcut. And the MOSFET-driven MXR 5150 Overdrive—which was designed by Bob Cedro with input from Mr. Van Halen himself—is a stab at harnessing Eddie’s hot-rodded, high-gain sounds in a pedal.

That’s no mean feat, given that EVH has traditionally been an amp overdrive dude. But the MXR often hits the mark through the use of a flexible set of EQ, drive, and gating controls—as well as a multi-gain-stage design that makes the pedal versatile beyond strictly Eddie-centric applications.

Bigger Box, Bolder Sounds The 5150 is reminiscent of MXR’s killer big box effects from the ’70s as well as the more recent MXR EVH-117 Flanger. It’s decked out in Eddie’s classic “racing stripe” livery. (Is it now possible to create an entire signal chain in this paint scheme? If there isn’t a cable yet someone should get on it!) The control panel features a common overdrive control set: output, bass, mid, treble, and gain. But there are also two smaller controls: a mini-button for 'boost' (which actually adds a little gain and compression,) and a small knob and a small knob for MXR’s Smart Gate noise gate that turns yellow when activated.

Diver Brown I tested the 5150 Overdrive with a humbucker-equipped “Super Strat” as well as a traditional, single coil-equipped Stratocaster through the clean channel of a Mesa/Boogie Mark IV. At its lowest gain setting (around 6:30) and with all the tone controls at noon, the MXR turned the Boogie into something more like a cranked tweed Fender—not a stretch, given the Boogie’s design pedigree, but a beautiful, rich distortion sound. Chords took on an aggressive snarl that would excel in a hard rock or classic rock rhythm setting. To get less bite and cleaner tones you need a soft touch, but the fact that approach works is a testament to how dynamic the pedal can be. It’s also surprisingly sensitive: moving the gain up just a hair to around 7 o’clock means a distinct increase in saturation and sustain that’s cool for smoother, more polite lead sounds or heavy rhythm tones.

Move the gain knob to noon and you’re squarely in the distortion camp—verging on the realms of Eddie’s storied in-your-face “Brown Sound.” Here, it’s hard to resist boogie-inflected moves like the lead riff for “Beautiful Girls.” Low, open-string chugs feel punchy and articulate, and the individual notes of chords ring true and clear, which does wonders for big chords with a lot of low-end like Fmaj7#11 or inversions like D/F# and E/G#. The extra clarity found me exploring sonorities and chord clusters that I ordinarily wouldn’t touch with this much gain. For leads, this setting was wicked. Pinch harmonics popped with ease, and tremolo-picked, single-note melodies way up on the fretboard sounded triumphant.

Some of my favorite Van Halen moments occur when Eddie works the shades between clean and dirty sounds in a song, and the MXR is responsive in a way that makes these shades available with a slight shift in guitar volume. And I could move from a massive wall of sound to the familiar Van Halen, quiet, clean-ish rhythm (think of the interlude after the “House of Pain” solo, or the intro of “Drop Dead Legs”) with just a flick of the guitar volume control.

Maxing the gain generates massive sounds that could be mistaken for a raging stack of amps. For modern metal rhythms, the sound is tight and especially potent. Soloing also felt amazingly easy with this much gain, and with the noise gate keeping stray harmonics and noise under control, a lot of inconvenient mistakes became a lot less pronounced! That said, the superb definition and focus of the pedal rewarded precision. Alternate picked, scalar sequences popped with percussiveness like a typewriter in the hands of a transcription wiz. Most other pedals or ultra high-gain amps would turn into a nebulous blob of noise at this point. The 5150 Overdrive stayed exceptionally open and detailed.

The added compression and gain from the 'boost' function adds a slight but perceptible bump (+6 dB.) Predictably, it doesn’t feel quite like a boost in the most familiar sense. Instead it feels more like an additional texture—adding dimension and a little extra harmonic breadth to an already very happening sound.

Noise Police When you use a lot of gain, you get a lot of noise. Usually, I’ll tame the noise (if it can be tamed) via muting techniques. With the 5150 Overdrive’s smart gate engaged, the pedal is so quiet that I sometimes forgot it was on. To really test the gate, I plugged in my Stratocaster, which can be unbearably noisy. It did wonders mitigating the Strat’s pesky hum, even with the gate set at near-minimum levels. The feature is a major plus. After using this pedal for a few weeks, it was almost hard to go back to a gate-less setup.

The Verdict Eddie Van Halen’s playing has always been about inventiveness, and the 5150 takes a pretty inventive approach to the overdrive pedal template. While the 5150 name might imply that it’s strictly a “Brown-Sound-in-a-box” device, it’s far from one-dimensional. This little box can deliver virtually any overdrive/distortion sound with a vengeance.

The 5150 Overdrive’s near $200 price tag might be a little more than consumers are used to from MXR. But the fact that this pedal can decimate many boutique pedals that do much less makes it a killer buy.

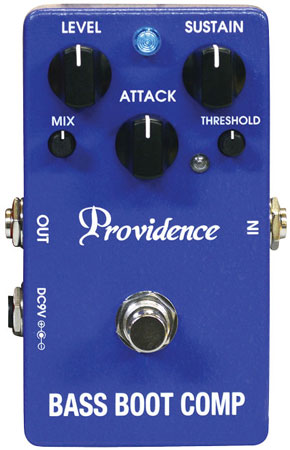

Compression isn’t the sexiest effect to talk about, but it’s a must-have (or should-have) for many a bassist. A good compressor will even out dynamics and bring life to tone for veteran players—not just lipstick a less-than-awesome right hand technique. Japan’s Providence has recently jumped into the bass compression game and loaned us their Bass Boot Comp for a look.

Compression isn’t the sexiest effect to talk about, but it’s a must-have (or should-have) for many a bassist. A good compressor will even out dynamics and bring life to tone for veteran players—not just lipstick a less-than-awesome right hand technique. Japan’s Providence has recently jumped into the bass compression game and loaned us their Bass Boot Comp for a look. It’s easy to overlook the virtues of a good acoustic amplifier. Having one isn’t essential to enjoying your guitar at home or around a campfire. And any performance space with a microphone (or two, if you sing) and a PA will probably get your performance over to the crowd.

It’s easy to overlook the virtues of a good acoustic amplifier. Having one isn’t essential to enjoying your guitar at home or around a campfire. And any performance space with a microphone (or two, if you sing) and a PA will probably get your performance over to the crowd. The control set is a straightforward affair that’s pretty easy to navigate. There’s a single volume knob, a three-band EQ, and reverb and effects-level controls for each of the amplifier’s channels. Each channel has a phase button if you run into trouble with feedback. The third, middle set of controls is for the amp’s effects and the SFX functionality, which, as we’ll see, enhances the sound of the amp in profound ways. The effects set includes a simple one-repeat delay, a multi-repeat delay, chorus, and vibrato. Each is tap-tempo enabled and can be bypassed via an optional footswitch or by turning the effects knob to zero.

The control set is a straightforward affair that’s pretty easy to navigate. There’s a single volume knob, a three-band EQ, and reverb and effects-level controls for each of the amplifier’s channels. Each channel has a phase button if you run into trouble with feedback. The third, middle set of controls is for the amp’s effects and the SFX functionality, which, as we’ll see, enhances the sound of the amp in profound ways. The effects set includes a simple one-repeat delay, a multi-repeat delay, chorus, and vibrato. Each is tap-tempo enabled and can be bypassed via an optional footswitch or by turning the effects knob to zero. It’s no secret that many “artist signature” guitars aren’t all that different from a company’s stock models. Jigger with surface cosmetics, maybe tweak the electronics a bit, and voilà — you’ve got a “new” model to sell at an upmarket price.

It’s no secret that many “artist signature” guitars aren’t all that different from a company’s stock models. Jigger with surface cosmetics, maybe tweak the electronics a bit, and voilà — you’ve got a “new” model to sell at an upmarket price.

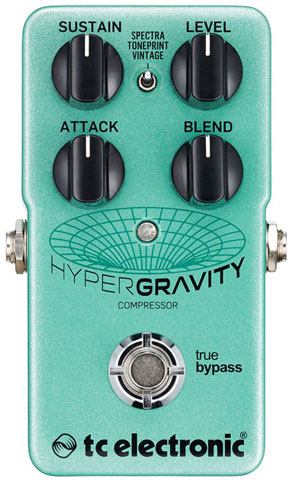

Leave it to TC Electronic to deliver an affordable pedal compressor with a twist. For the new Tone Print-enabled HyperGravity, they’ve borrowed the algorithm from their System 6000 studio multiband compressor. The results often sound quite unlike any other stomp comp.

Leave it to TC Electronic to deliver an affordable pedal compressor with a twist. For the new Tone Print-enabled HyperGravity, they’ve borrowed the algorithm from their System 6000 studio multiband compressor. The results often sound quite unlike any other stomp comp. Universal Audio’s rack-mountable Apollo audio interface was an hit upon its 2012 release. Its stellar preamps, lucid design, and innovative software were perfect fits for project studios requiring great-sounding components and flexible operation, but not a vast number of preamps. (The original Apollo has four, plus additional analog and digital line inputs.)

Universal Audio’s rack-mountable Apollo audio interface was an hit upon its 2012 release. Its stellar preamps, lucid design, and innovative software were perfect fits for project studios requiring great-sounding components and flexible operation, but not a vast number of preamps. (The original Apollo has four, plus additional analog and digital line inputs.) At last winter’s NAMM show in Anaheim, California, D’Angelico Guitars unveiled a line of steel-string flattop acoustics with names like Gramercy, Mercer, Lexington, and Madison. These are, of course, references to locales in Manhattan, where the legendary luthier John D’Angelico built the finest archtops to order from the 1930s until his death in 1964.

At last winter’s NAMM show in Anaheim, California, D’Angelico Guitars unveiled a line of steel-string flattop acoustics with names like Gramercy, Mercer, Lexington, and Madison. These are, of course, references to locales in Manhattan, where the legendary luthier John D’Angelico built the finest archtops to order from the 1930s until his death in 1964. Introduced in 1994, the original Ibanez Talman remained in production just a few years before it was discontinued. It arrived on a wave of interest in offbeat ’60s models. And along with guitars like the Charvel Surfcaster, it attracted shoegazers, indie-, and noise-rock artists looking for a synthesis of modern stability and vintage aesthetics. In the short time it was produced, and in the years since, the Talman gained a quietly devoted cult following.

Introduced in 1994, the original Ibanez Talman remained in production just a few years before it was discontinued. It arrived on a wave of interest in offbeat ’60s models. And along with guitars like the Charvel Surfcaster, it attracted shoegazers, indie-, and noise-rock artists looking for a synthesis of modern stability and vintage aesthetics. In the short time it was produced, and in the years since, the Talman gained a quietly devoted cult following. You can run both DIs at the same time—one clean and one dirty. You don’t have to have a splitter to lay down one clean take while you are using the amp to saturate tone. Whether you’d like to blend the signal or need to fix something later on the clean track, the option is there. Pretty killer.

You can run both DIs at the same time—one clean and one dirty. You don’t have to have a splitter to lay down one clean take while you are using the amp to saturate tone. Whether you’d like to blend the signal or need to fix something later on the clean track, the option is there. Pretty killer. Although the Octa-Switch MK2 still feels fresh in our memory, Carl Martin recently released the MK3, a streamlined edition of the popular MK2. At a street price of around $427, it’s easily the most affordable switcher in our roundup.

Although the Octa-Switch MK2 still feels fresh in our memory, Carl Martin recently released the MK3, a streamlined edition of the popular MK2. At a street price of around $427, it’s easily the most affordable switcher in our roundup. MXR’s Eddie Van Halen signature phaser, flanger, and wah pedals made elements of Eddie’s tone available and affordable to the masses. But one of the most critical components in creating his “Brown Sound” is copious amp overdrive. If you don’t have a vintage Marshall Super Lead or an EVH amp (both expensive propositions), the right overdrive pedal is an effective shortcut. And the MOSFET-driven MXR 5150 Overdrive—which was designed by Bob Cedro with input from Mr. Van Halen himself—is a stab at harnessing Eddie’s hot-rodded, high-gain sounds in a pedal.

MXR’s Eddie Van Halen signature phaser, flanger, and wah pedals made elements of Eddie’s tone available and affordable to the masses. But one of the most critical components in creating his “Brown Sound” is copious amp overdrive. If you don’t have a vintage Marshall Super Lead or an EVH amp (both expensive propositions), the right overdrive pedal is an effective shortcut. And the MOSFET-driven MXR 5150 Overdrive—which was designed by Bob Cedro with input from Mr. Van Halen himself—is a stab at harnessing Eddie’s hot-rodded, high-gain sounds in a pedal.

Gear reviewers tend to describe new amps in terms of old ones. We rely on stock phrases: “Vox-like chime,” “Blackface-style scoop,” “Marshall-like midrange.” That usually works out fine, because new amps also tend to rely on what’s come before. But comparisons aren’t so easy when confronted with an amp as unique, idiosyncratic, and just plain weird as Siegmund’s massive Doppler combo. I’ve never encountered anything like it, and I bet you haven’t either.

Gear reviewers tend to describe new amps in terms of old ones. We rely on stock phrases: “Vox-like chime,” “Blackface-style scoop,” “Marshall-like midrange.” That usually works out fine, because new amps also tend to rely on what’s come before. But comparisons aren’t so easy when confronted with an amp as unique, idiosyncratic, and just plain weird as Siegmund’s massive Doppler combo. I’ve never encountered anything like it, and I bet you haven’t either.